My

best friend, – for over thirty years - died about a decade ago. In addition to

fond memories, she left me her words of wisdom, aphorisms from her childhood in

pre-Nazi Europe. I can occasionally dredge one up but unfortunately, didn’t

write them down at the time and have forgotten most of them.

Dina

Pisé was born in Lithuania in the late 1920s. Her idyllic childhood came to an

end when the Nazis invaded her home town, Kovna, murdering her father and

brother while she watched and sending her and her mother to a German work camp

where she spent the remainder of the war. Weeks before they were to be

liberated, her mother died of typhus fever. Not the most auspicious way to

enter adulthood but a testimonial to how human beings can live through

unbelievably dire experiences. She not only survived, she lived life to the

fullest, refusing to dwell on the horrors she had witnessed. She would not

participate in Shoah memorials; the past was dead and as far as she was concerned,

would stay that way. I remember her saying that the Nazis had robbed her of her

childhood and she was not giving them any more of her life.

After

coming to this country from a DP camp in Germany, she married, had a child,

divorced and remarried a brilliant French entrepeneur and became an artist. She

was exotically beautiful, had lots of friends and lovers, gave great parties

where she cooked marvelous Eastern European food, played the guitar and sang

melancholy Russian love songs. Her Friday night poker games were legendary, a

“hot ticket” invite; only men, no wives allowed. (if you knew their wives, you

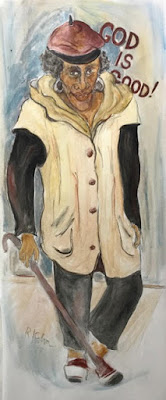

wouldn’t have invited them either). Most of all she became a sculptor, creating

a house full of life-sized figures made of paper mache or stuffed muslin. Her

work was wise and loving and witty, a chance to recreate in art some of what

she had lost in life.

I

still remember some of her sayings, and, like most folk wisdom, they were

remarkably accurate. I think most of

them were Russian or Yiddish in origin, but universal in meaning. At one time,

I thought about collecting them and turning them into a book, but

unfortunately, I never got around to it, and then she was gone. I have forgotten most of them, but every once

in a while one will pop into my head. Although it’s a little late, I’ve started

writing them down and thought I’d share a few that I remember:

1)

Three heads can’t sleep on

one pillow.

Meaning, we never really know the truth of

what goes on in someone else’s life. And, as far as marriages are concerned,

you can never believe what the couple tells you. Even the two heads involved

have trouble figuring it out.

2)

She exchanged good shoes for

slippers.

This

was her comment about a friend of ours who was noted for having frivolous

lovers, none of whom were equal in quality to her rather dull but devoted

husband. (see #1)

3)

If he were mine I would

drown him.

This

referred to my late husband who got on her nerves.

The

images in this post were taken of the two of us about forty years ago for a

joint exhibit held at the Art Barn in Greenwich. We even looked like sisters.